The UK is the third-largest ecommerce market in the world, with online retail now accounting for over 38% of total retail sales. As digital commerce grows more complex, the platforms behind it need to keep pace. That is where ecommerce microservices architecture comes in.

Globally, 74% of organisations already use microservices architecture, with UK retailers leading the charge: 85% of UK ecommerce businesses have adopted headless or composable architecture, the highest rate of any country. This guide explains what microservices architecture means for ecommerce, how it compares to the monolithic approach most businesses start with, and when it makes sense to adopt. Whether you are running a Shopify store processing thousands of orders or building a custom platform from scratch, understanding these architectural choices will help you make better decisions about how your ecommerce technology scales.

1. What is ecommerce microservices architecture?

Ecommerce microservices architecture is a way of building online retail platforms as a collection of small, independent services rather than one large application. Each service handles a single business function, such as managing the product catalogue, processing payments, or tracking inventory, and operates independently of the others.

These services communicate with each other through well-defined APIs (application programming interfaces) and messaging systems. They can be developed by different teams, written in different programming languages, and deployed on different schedules. If the payment service needs an update, you deploy just that service. The rest of the platform carries on without interruption.

The concept comes from broader software engineering principles, particularly domain-driven design (DDD), which encourages organising software around real business domains rather than technical layers. In ecommerce, these domains map naturally to the things your business actually does: listing products, managing stock, processing orders, handling payments, and shipping goods.

In plain terms: Think of a monolithic platform as a single machine where every gear is connected. If one gear breaks, the whole machine stops. Microservices are more like a team of specialists, each doing their own job. If one person is ill, the rest of the team keeps working.

Key characteristics

- Independent deployment — each service has its own code repository, build process, and deployment pipeline. Teams release updates without waiting for other teams.

- Decentralised data — each service manages its own database, choosing the storage technology best suited to its needs (the "database-per-service" pattern).

- API-first communication — services interact through defined contracts, not by directly accessing each other's code or databases.

- Bounded contexts — each service owns a clear business domain with its own terminology and rules, preventing confusion across teams.

- Containerisation — services are typically packaged in Docker containers and managed by orchestration tools like Kubernetes, ensuring consistent behaviour across environments.

2. Monolith vs microservices: how they compare

Most ecommerce platforms start life as monoliths, and for good reason. A monolithic architecture bundles the entire application — product listings, shopping cart, checkout, payment processing, inventory management — into a single codebase that shares one database. This is simpler to build, test, and deploy when you are starting out.

The problems emerge as the business grows. In a monolith, a bug in the product search feature can crash the entire checkout process because everything runs in the same application. Scaling means provisioning more resources for the whole application, even if only one function is under pressure. And deploying a small change to pricing logic means redeploying everything, with all the risk that entails.

| Aspect | Monolithic architecture | Microservices architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Codebase | Single codebase, all functions together | Separate codebases per service |

| Database | Shared database for all functions | Each service owns its own database |

| Deployment | Deploy entire application for any change | Deploy individual services independently |

| Scaling | Scale the whole application | Scale individual services based on demand |

| Fault isolation | One bug can crash everything | Failures contained to individual services |

| Technology choice | One tech stack for everything | Best technology for each service's needs |

| Team structure | Teams organised by technical layer | Teams organised around business domains |

| Initial complexity | Lower — simpler to start | Higher — requires infrastructure investment |

| Operational complexity | Lower — one thing to monitor | Higher — many services to manage |

| Time to market | Slows as application grows | Faster — teams work in parallel |

| Best suited for | Small teams, early-stage products, simple domains | Large teams, complex domains, high-scale operations |

Important: Monolithic architecture is not inherently bad. Many successful ecommerce businesses run on well-structured monoliths. The question is not "should we use microservices?" but rather "have we outgrown our current architecture?" If your deployment cycles are measured in weeks, if scaling is getting expensive, or if teams are stepping on each other's toes, then microservices may be worth exploring.

3. Core ecommerce microservices

An ecommerce platform can be decomposed into several core services, each aligned with a distinct business domain. Here is what each one does and why it benefits from being independent.

Product catalogue service

The product catalogue service is the single source of truth for all product data: titles, descriptions, images, attributes, categories, and pricing information. When your merchandising team updates a product listing, the change flows through this service to the rest of the platform.

Other services query the catalogue when they need product information. The search service indexes catalogue data for fast lookups. The inventory service references product identifiers when tracking stock. The recommendation engine uses product attributes to suggest related items.

By keeping catalogue management separate, your team can update product data without risking disruption to checkout, payments, or any other function.

Inventory management service

The inventory service tracks stock levels across warehouses, sales channels, and suppliers in real time. It handles stock reservations when customers add items to their carts, prevents overselling by ensuring availability checks happen atomically, and manages stock allocation across multiple fulfilment locations.

This service operates under extreme concurrency pressure during peak events like Black Friday or Boxing Day sales. Thousands of customers checking stock and placing orders simultaneously demands a service that can respond in milliseconds. Dedicated inventory services often use specialised data stores like Redis for the speed required, rather than general-purpose relational databases.

Real-world relevance: Inventory accuracy is one of the most common pain points for UK ecommerce businesses. We have covered the consequences of poor inventory synchronisation in our guide to common ecommerce integration mistakes, where overselling alone costs retailers over £1.3 trillion globally each year.

Order management service

The order management service orchestrates the entire order lifecycle: placement, payment authorisation, inventory reservation, picking, packing, dispatch, and delivery tracking. It is the coordinator that brings other services together for each transaction.

This service handles distributed transactions across multiple services. If payment succeeds but inventory reservation fails, the order service must trigger compensating actions to reverse the payment. It implements idempotent operations to handle network failures gracefully, ensuring orders are not duplicated if requests are retried.

Payment processing service

The payment service manages the security-sensitive process of accepting payments, authorising transactions through external gateways (Stripe, PayPal, Worldpay), processing refunds, and handling fraud detection. PCI DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard) compliance mandates strict controls on how payment data is handled, stored, and transmitted.

By isolating payment processing in its own service, you limit the scope of PCI compliance to one component rather than the entire platform. The payment service acts as an abstraction layer, so the rest of your platform does not need to know which payment gateway you use. Switching from Stripe to Adyen, or adding Apple Pay alongside card payments, becomes a change within one service rather than a platform-wide project.

Shipping and fulfilment service

The shipping service manages everything from carrier selection and label generation to tracking updates and returns processing. It integrates with carrier APIs from Royal Mail, Parcelforce, DHL, FedEx, and others to provide shipping options, calculate delivery costs, and track parcels in transit.

Different carriers serve different needs. Domestic parcels might route through Royal Mail for cost efficiency, whilst international orders use DHL for reliability. The shipping service abstracts these carrier differences, so the order service simply requests shipment without needing to understand carrier-specific APIs.

Customer and authentication service

The customer service handles user registration, authentication (login), profile management, and access control. When customers log in, they authenticate through this service, which issues JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) granting access to other services. Centralising authentication ensures consistent security policies across the entire platform.

This service also manages customer preferences, communication settings, and GDPR-related data requests. Under UK GDPR, when a customer requests data erasure, you need to coordinate deletion across every integrated system. Having a central customer service makes it clear where the authoritative customer record lives.

Search and recommendation services

The search service maintains an optimised index of product data (typically using Elasticsearch) to support fast keyword search, filtering, and sorting. Rather than querying the product catalogue database directly, which would be prohibitively slow for full-text search, the search service maintains its own denormalised copy of product data structured specifically for search performance.

Recommendation services analyse browsing history, purchase patterns, and product similarities to generate personalised suggestions. These are computationally intensive operations that benefit from running independently, so they can scale based on their own workload without affecting core commerce functions.

4. Architecture patterns and communication

Understanding the patterns that connect microservices is essential to making the architecture work in practice. This section covers the key architecture layers and how services communicate.

Architecture layers

A typical ecommerce microservices architecture is organised into layers:

- Client layer — the storefront that customers interact with (web, mobile app, or progressive web app). In a microservices architecture, the frontend often calls a single entry point rather than individual services directly.

- API gateway — a central entry point that routes requests from clients to the correct backend services. The gateway handles cross-cutting concerns like authentication, rate limiting, request logging, and SSL termination, so individual services do not need to duplicate this logic.

- Service layer — the individual microservices (catalogue, inventory, orders, payments, shipping, etc.) that implement business logic.

- Data layer — the databases and data stores owned by each service. In the database-per-service pattern, each service chooses the database technology best suited to its needs.

Synchronous communication: REST and gRPC

Synchronous communication is used when a service needs an immediate response to proceed. The most common approach is REST APIs, which use standard HTTP methods (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) to operate on resources. When the shopping cart service needs to check whether a product is in stock, it makes a synchronous GET request to the inventory service and waits for the response.

gRPC offers a higher-performance alternative for service-to-service communication, using Protocol Buffers for compact binary serialisation and HTTP/2 for multiplexed connections. gRPC is well suited to internal communication between services where low latency matters, but REST remains the standard for public-facing APIs due to its simplicity and broad tooling support.

Trade-off: Synchronous calls create temporal coupling. If the inventory service is slow or unavailable, the shopping cart service is blocked. Chains of synchronous calls can cascade failures across the system. Use synchronous communication only where you genuinely need an immediate response.

Asynchronous communication: message queues and events

Asynchronous communication decouples services by using message brokers like RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka, or AWS SQS. Instead of calling another service directly, a service publishes a message or event to a broker. Other services subscribe to the messages they care about and process them independently.

For example, when the order service creates an order, it publishes an "OrderCreated" event. The inventory service subscribes to this event and reserves stock. The payment service subscribes and processes payment. The notification service subscribes and sends a confirmation email. Each service processes the event on its own schedule, and if one service is temporarily unavailable, messages queue until it recovers.

This event-driven approach naturally supports the saga pattern, which manages distributed transactions across services. Here is how a typical order processing saga flows:

- Order service creates order (status: PENDING) and publishes

OrderCreated - Payment service receives event, processes payment, publishes

PaymentSucceeded - Inventory service receives event, reserves stock, publishes

InventoryReserved - Shipping service receives event, schedules shipment, publishes

ShippingScheduled - Order service receives event, updates status to CONFIRMED, sends customer notification

If any step fails, compensating events reverse the previous steps. Payment failed? No inventory gets reserved. Inventory unavailable? A refund is triggered automatically. Each service handles its own rollback logic, maintaining consistency without a central transaction coordinator.

Choreography vs orchestration: The example above uses choreography, where services react to events independently. An alternative is orchestration, where a central orchestrator explicitly directs each step. Choreography is simpler and more loosely coupled, but harder to debug. Orchestration provides better visibility and control, but introduces a central point of coordination. Most ecommerce platforms use orchestration for critical flows like checkout and choreography for less critical operations like notifications and analytics.

The database-per-service pattern

In microservices architecture, each service manages its own database. This is a deliberate design choice that promotes loose coupling: services cannot bypass APIs by querying each other's databases directly. It also lets each team choose the storage technology best suited to their workload:

- Product catalogue — PostgreSQL or MongoDB for structured/semi-structured product data

- Inventory — Redis for microsecond-level stock lookups under high concurrency

- Orders — PostgreSQL for transactional integrity of order records

- Search — Elasticsearch for full-text search and faceted filtering

- Analytics — ClickHouse or BigQuery for analytical queries across large datasets

The trade-off is that you lose the simplicity of ACID transactions across multiple domains. Cross-service consistency requires patterns like sagas, event sourcing, or CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation), which add architectural complexity.

MACH and composable commerce

You may encounter the term MACH architecture (Microservices, API-first, Cloud-native, Headless) when researching ecommerce platforms. MACH is not a separate architecture from microservices; it is a broader set of principles that includes microservices as one of four pillars. The "composable commerce" approach builds on MACH by assembling best-of-breed services from different vendors (commercetools for commerce, Contentful for content, Algolia for search) rather than buying everything from a single platform.

The UK leads globally in composable adoption, with 85% of UK ecommerce businesses using headless architecture compared to 72% in Australia and 68% in the US. According to the MACH Alliance's 2025 research, 91% of organisations increased their MACH infrastructure in the past year, and by 2027, an estimated 60% of new digital commerce solutions will align with MACH principles. Even traditionally monolithic platforms like Shopify (Hydrogen/Oxygen) and Salesforce (Composable Storefront) are adapting to support composable approaches.

5. Benefits for ecommerce businesses

The benefits of microservices architecture are most pronounced for ecommerce businesses that have outgrown their monolithic platforms. Here is what the shift delivers in practice.

These figures come from a cross-industry study of organisations that completed ecommerce microservices migrations. The results are impressive, but they reflect mature implementations with strong engineering teams. The benefits compound over time as teams become more proficient with the architecture.

Independent scaling

During a flash sale, your product search and checkout services might need ten times their normal capacity, whilst the returns and customer profile services tick along as usual. Microservices let you scale just the services under pressure, rather than provisioning additional resources for the entire application. On cloud platforms like AWS or Azure, this scaling can be automated based on real-time demand metrics, scaling up within seconds and scaling back down when traffic subsides.

The numbers bear this out: organisations using microservices report handling 3.7 times their normal peak traffic without performance degradation, compared to 1.8 times with monolithic architectures. Amazon's product detail page service, for example, scales automatically from 450 instances during normal operations to 2,200 instances during peak events like Prime Day, processing 93 million requests daily whilst maintaining response times below 300ms.

Fault isolation and resilience

In a monolith, a memory leak in the product recommendation engine can bring down the entire store, including checkout. In a microservices architecture, that failure is contained. Customers can still browse and buy; they just will not see personalised recommendations until the recommendation service recovers. Circuit breaker patterns automatically detect failing services and stop sending requests to them, preventing cascading failures across the system.

The reliability improvements are significant: organisations report a 76% reduction in annual system downtime after migrating to microservices, dropping from an average of 43 hours of downtime per year to around 10 hours. For large ecommerce operations, each percentage point of additional uptime translates to roughly $2.1 million in avoided lost sales annually.

Technology flexibility

Different problems benefit from different tools. Your inventory service might perform best with Redis for in-memory speed, whilst your order service needs the transactional guarantees of PostgreSQL, and your search service runs on Elasticsearch. Microservices let each team choose the best technology for their specific challenge rather than forcing every function into a single technology stack.

Faster time to market

When teams own independent services, they can develop, test, and deploy features without waiting for other teams. The payment team can roll out support for a new payment method whilst the catalogue team simultaneously updates product attribute handling. This parallel development significantly reduces the time from idea to production, which matters in a competitive market where UK online retail is growing at nearly 10% annually.

The deployment frequency gains are substantial. Organisations migrating to microservices report a 430% increase in deployment frequency, with major feature implementations dropping from an average of 11.2 weeks to 3.7 weeks. At the extreme end, Amazon went from 1,079 deployments per quarter to over 136,000 deployments per day once its microservices migration was complete.

Easier integration with third-party services

Ecommerce platforms rarely exist in isolation. They connect to ERP systems, CRM tools, marketing platforms, fulfilment providers, and payment gateways. Microservices make these integrations cleaner because each integration point is handled by a dedicated service with a defined API contract. Adding a new fulfilment provider means updating the shipping service, not touching the core platform. For more on getting integrations right, see our complete guide to system integration.

6. Challenges and trade-offs

Microservices solve real problems, but they create new ones. Being honest about the trade-offs is essential for making a sound architectural decision.

Data consistency across services

In a monolith with a single database, you can wrap multiple operations in a database transaction and guarantee consistency. In microservices, where each service owns its data, there is no single transaction spanning the order, inventory, and payment services. You must use patterns like sagas, where each service performs its local transaction and publishes events for the next step. If something fails, compensating transactions undo previous steps.

This introduces eventual consistency: data across services will become consistent, but not necessarily immediately. For many ecommerce operations this is acceptable, but it requires careful design and thorough testing.

Operational complexity

Instead of monitoring and maintaining one application, you now have dozens (or hundreds) of independent services, each with its own logs, metrics, deployment pipeline, and potential failure modes. You need centralised logging, distributed tracing, and comprehensive monitoring to understand what is happening across the system. A single customer request might flow through five or six services, and debugging issues requires tracing that request through all of them.

Tools like OpenTelemetry, Prometheus, and Grafana help manage this complexity, but they require expertise to set up and maintain. For small teams, this overhead can outweigh the benefits.

Team structure requirements

Microservices work best when teams are organised around business domains ("you build it, you run it"). The payment team owns the payment service end-to-end, from development through deployment and on-call support. This requires engineers who are comfortable with full-stack ownership, including infrastructure, monitoring, and incident response, not just writing code.

Small teams of two or three developers often lack the capacity to manage multiple independent services alongside their daily development work. Most organisations find that microservices require a minimum of 10-15 engineers to be sustainable.

The distributed monolith trap

The most destructive anti-pattern in microservices is the distributed monolith: services that are deployed independently but remain tightly coupled through shared databases, excessive synchronous calls, or coordinated deployments. You get the operational complexity of distributed systems with all the coupling problems of a monolith. It is the worst of both worlds.

This happens when service boundaries are drawn incorrectly, when services share databases, or when teams default to synchronous REST calls for everything. One company that consolidated from 25 microservices to 5 well-designed services achieved an 82% reduction in cloud infrastructure costs and saw response times improve from 1.2 seconds to 89 milliseconds. The lesson: more services does not mean better architecture.

Security across distributed services

A monolith has one attack surface. Microservices have many. Every service-to-service API call is a potential vulnerability, and the OWASP API Security Top 10 lists broken object-level authorisation as the number one concern for API-driven architectures. Securing microservices requires a zero-trust approach where no service is trusted by default, even within the internal network.

In practice, this means implementing mutual TLS (mTLS) for all service-to-service communication, where both the calling and receiving service must present valid certificates before any data is exchanged. Service meshes like Istio and Linkerd handle this automatically through sidecar proxies, removing the burden from application code. For ecommerce platforms handling payments, PCI DSS 4.0 compliance becomes more complex with microservices, as you must clearly define which services fall within the cardholder data environment and enforce multi-factor authentication for all access to those components.

Monitoring and observability

When a customer reports a slow checkout, tracing the issue through a monolith means examining one application's logs. In a microservices architecture, that checkout request may have touched six or seven services, and the bottleneck could be in any of them. Distributed tracing (using tools like OpenTelemetry, Jaeger, or Zipkin) follows requests across service boundaries by propagating trace identifiers through every call, so you can see exactly where time is being spent.

Effective observability rests on three pillars: logs (what happened), metrics (how things are performing), and traces (the path a request took). OpenTelemetry has become the industry standard for instrumentation, offering vendor-neutral telemetry collection that avoids lock-in to any specific monitoring platform. The trade-off is cost: service meshes themselves add latency (Linkerd adds roughly 1ms per hop; Istio adds 3-10ms), and the volume of telemetry data from dozens of services requires careful management to avoid runaway monitoring bills.

When microservices are NOT the right choice

Consider staying with a monolith if:

- Your team has fewer than 10-15 developers

- Your application is relatively simple with predictable, moderate traffic

- You lack DevOps maturity (no CI/CD pipelines, no container orchestration, limited monitoring)

- You are a startup still validating your business model and need to iterate rapidly

- Your current monolith is well-structured and still serving business needs

A well-structured monolith is not a failure. It is a deliberate architectural choice that reduces complexity and operational overhead. The modular monolith, where code is organised into well-defined modules with clear boundaries but deployed as a single unit, offers many of the organisational benefits of microservices without the distributed systems complexity. It is often the best stepping stone for teams that may eventually need microservices but are not ready for the operational investment today.

7. Migration strategies

Migrating from a monolith to microservices is not an all-or-nothing decision. The most successful migrations happen incrementally, extracting one service at a time whilst the monolith continues to handle everything else.

The strangler fig pattern

Named after the tropical fig that gradually grows around a host tree, the strangler fig pattern involves building new functionality as microservices that sit alongside the existing monolith. Over time, more functionality migrates to microservices, and the monolith shrinks until it can eventually be retired (or remains as a thin wrapper).

The process works like this:

- Identify a bounded context — choose a business domain that is relatively self-contained, such as inventory management or customer authentication.

- Build the new service — implement the chosen domain as a standalone microservice with its own database and API.

- Route traffic — use an API gateway or proxy to direct requests for that domain to the new service instead of the monolith.

- Retire the old code — once the new service is handling production traffic reliably, remove the corresponding code from the monolith.

- Repeat — choose the next bounded context and repeat the process.

Why this works: The strangler fig pattern keeps your existing system running throughout the migration. There is no "big bang" cutover. If the new service has problems, you can route traffic back to the monolith. Teams build confidence and learn microservices patterns incrementally, reducing the risk of a failed migration.

Choosing what to extract first

Start with a service that is:

- High-value — addresses a real pain point (e.g. inventory that needs independent scaling during sales events)

- Well-bounded — has clear interfaces with the rest of the system and minimal cross-cutting concerns

- Low-risk — not your most critical path (avoid starting with payments or checkout)

Common first extractions include inventory management, product search, and notification services, as these tend to have well-defined boundaries and clear scaling requirements.

The modular monolith as a stepping stone

If your monolith is a tangled mess of interdependent code, jumping straight to microservices can make things worse. The modular monolith approach restructures your existing codebase into well-defined modules with clear boundaries and internal APIs, but keeps everything deployed as a single unit.

This gives you the organisational benefits of domain-driven design (clear ownership, well-defined interfaces) without the operational complexity of distributed systems. Once your modules have clean boundaries, extracting them into independent services later becomes a straightforward infrastructure change rather than a major refactoring effort.

Shopify proves the modular monolith works at scale: Shopify handles 173 billion requests in a single 24-hour period (Black Friday 2024), with peaks of 284 million requests per minute and 45 million database queries per second, all running on a 2.8 million line modular monolith rather than microservices. Instead of splitting into independent services, Shopify uses "Pods" (fully isolated slices, each with its own database and cache) for fault isolation and horizontal scaling. Their 400,000+ unit tests build in under 20 minutes. If a modular monolith can handle that scale, the question for most businesses is not whether they need microservices, but whether they have exhausted what a well-structured monolith can do.

How long does migration actually take?

Microservices migrations are measured in years, not months. Netflix began its migration in 2009 after a three-day database corruption incident and completed the transition to AWS in January 2016, a seven-year journey. BMW migrated over 1,300 microservices from on-premises infrastructure to AWS over three years (2019-2022), using a structured three-phase approach: preparation (standardising architecture and refactoring to Kubernetes), migration (executing with clear cloud-first directives), and optimisation (building shared platform services). Deliveroo's migration from its monolithic Heroku deployment to distributed services on AWS took roughly 12 months of focused effort.

For mid-market UK retailers, a realistic timeline is 12 to 24 months for the first phase of extraction, with the full migration continuing incrementally beyond that. Research shows that 62% of organisations report ROI challenges during the first 12 months of implementation, but those that conduct proper analysis before migration are 3.2 times more likely to achieve positive returns within 18 months. The lesson from every successful migration: plan carefully, start small, and measure results before expanding scope.

8. Real-world examples

Microservices architecture is not just theory. Here are examples of organisations that have adopted it, including several UK retailers.

Amazon

Amazon is often cited as the poster child for microservices migration. In the early 2000s, Amazon's monolithic application was becoming a bottleneck for innovation. The company famously decomposed its platform into hundreds of independent services, enabling the rapid feature development and massive scale that defines Amazon today. This architectural decision also led to the creation of Amazon Web Services (AWS), as the infrastructure tools built for internal use became products in their own right.

ASOS

ASOS migrated from an on-premises monolithic .NET application to approximately 30 microservices on Microsoft Azure, serving 23 million active customers across 200+ markets with over £3 billion in annual sales. The company reorganised into 35 development teams across 9 digital domains and 19 platforms, with each cross-functional team owning its services end-to-end. They used RESTful APIs for synchronous communication and Azure Service Bus for asynchronous messaging, with each service managing its own data store. The migration was gradual, not a "big bang", with feature flags routing traffic between legacy and new services.

Ocado

Ocado runs approximately 150 microservices to orchestrate thousands of autonomous robots in its automated warehouses. The robots receive position instructions up to ten times per second and move at four metres per second, passing within five millimetres of each other. The Warehouse Execution System, migrated to AWS, maintains sub-millisecond responsiveness despite running in the cloud. The Erith warehouse alone processes over 200,000 orders per week. Ocado licenses this platform to Kroger (US), Coles (Australia), and other grocers worldwide, turning a well-designed microservices platform into a revenue-generating product.

Deliveroo

Deliveroo started on a Ruby on Rails monolith that became the largest application ever deployed on Heroku: 1,800 CPU cores and 3 terabytes of memory at peak. As the team grew from 10 to 100 engineers and build times stretched from 7 minutes to over 2 hours, they migrated to a distributed architecture on AWS with strict rules: each service owns its data exclusively, with no shared databases. They use an event bus for asynchronous communication, with REST APIs for synchronous queries. The new architecture reduced food delivery times by 20%.

Tesco

Tesco, the UK's largest retailer, processes over 1.2 million online grocery orders per week and generates £6 billion in annual online sales. Their Whoosh rapid delivery service, built on microservices principles, delivers groceries from stores within 60 minutes. The service integrates real-time inventory visibility, Clubcard loyalty data from 16.5 million UK households, dynamic pricing, and carrier management, each running as independent capabilities. Tesco has invested approximately $2 billion annually in ICT, spanning cloud infrastructure, AI, and robotics.

MeldEagle: microservices for Shopify merchants

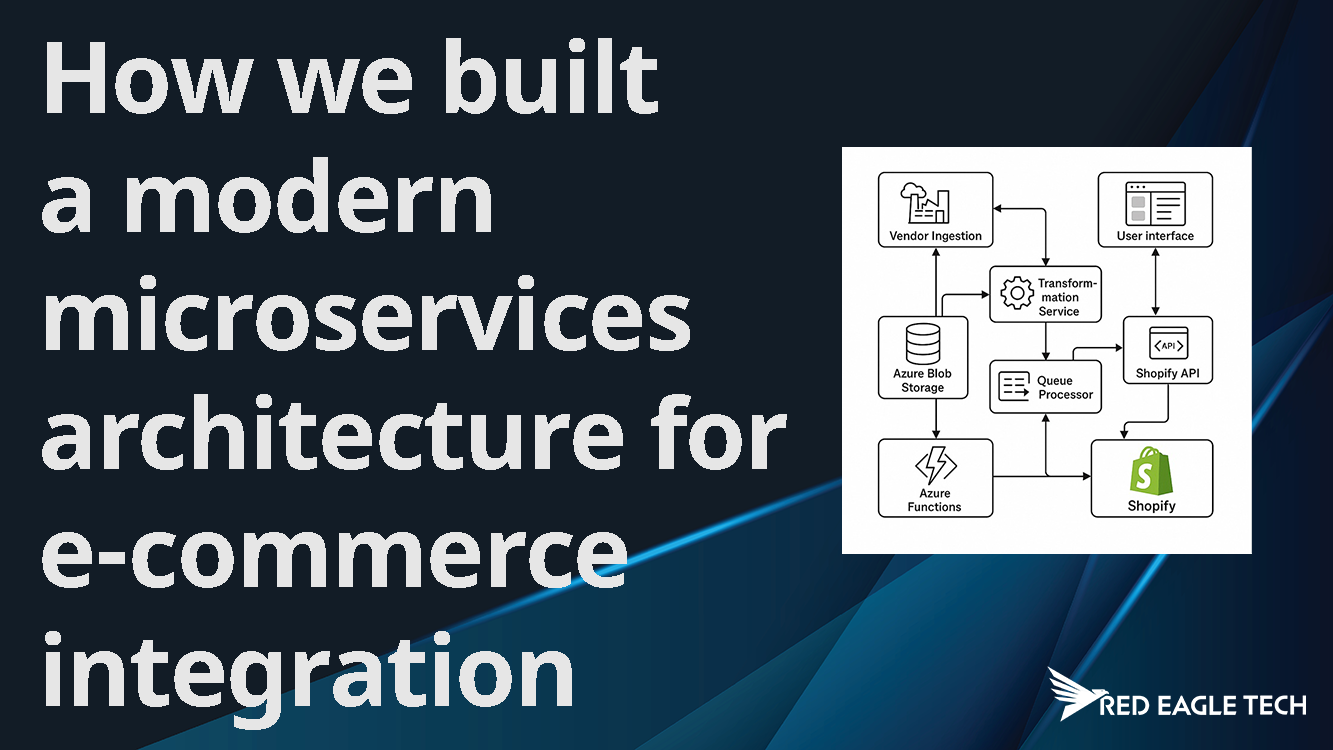

At Red Eagle Tech, we built MeldEagle using microservices architecture to give Shopify merchants enterprise-level automation without re-platforming. Independent services handle supplier integration, stock synchronisation, pricing rules, SEO optimisation, and data validation, each scaling independently based on workload.

We have documented the technical details of this build in our companion article: How we built a modern microservices architecture for ecommerce integration. That case study covers the specific technology choices, challenges, and lessons learned from building a real microservices platform for UK ecommerce.

9. Is this right for your business?

Deciding whether to adopt microservices is not a purely technical decision. It depends on your team size, business complexity, growth trajectory, and operational maturity. Here is a practical framework to help you assess readiness.

Readiness checklist

| Factor | Ready for microservices | Not ready yet |

|---|---|---|

| Team size | 15+ developers | Fewer than 10 developers |

| Deployment frequency | Need to deploy daily or multiple times per day | Comfortable with weekly or monthly deployments |

| Scaling needs | Different components have very different scaling requirements | Uniform scaling across the application is sufficient |

| DevOps maturity | CI/CD pipelines, container orchestration, centralised monitoring in place | Manual deployments, limited monitoring |

| Domain complexity | Complex business domains with distinct bounded contexts | Simple, well-understood domain |

| Team coordination | Teams frequently blocked by dependencies on other teams | Teams work well together with current structure |

Cost considerations

Microservices require investment beyond the initial build:

- Infrastructure — container orchestration (Kubernetes), message brokers, API gateways, service mesh tooling

- Monitoring and observability — distributed tracing, centralised logging, metrics dashboards

- Personnel — DevOps engineers, platform engineers, on-call rotations for each service

- Cloud spend — running many small services can be more expensive than one well-optimised monolith, particularly for low-traffic applications

Research shows that microservices require roughly 25% more resources than monolithic architectures due to operational complexity alone. A 50-service deployment might cost £150,000-£300,000 per year in personnel (2-4 dedicated DevOps/SRE engineers) plus £60,000-£120,000 in infrastructure overhead, compared to £100,000-£150,000 total for a modular monolith requiring 1-2 operations engineers. Debugging in distributed systems also takes roughly 35% longer than in monoliths.

For UK SMEs, the investment needs to be justified by clear business requirements. If your current platform handles your scale and your team can ship features at the pace your business needs, the cost of microservices may not deliver sufficient return.

Need help deciding? If you are considering a bespoke software development project and want to understand whether microservices are the right architecture for your needs, get in touch for an honest, no-obligation conversation. We will tell you if a simpler approach would serve you better. You can also use our bespoke software cost estimator to get an idea of the investment involved.